The Brilliant Climate Scientist History Forgot 0

Why Eunice Newton Foote’s legacy matters—especially now.

By Lindsay H. Metcalf, author of Footeprint: Eunice Newton Foote at the Dawn of Climate Science and Women's Rights

It’s been almost 170 years since Eunice Newton Foote discovered carbon dioxide’s atmosphere-warming properties—what we now know as the greenhouse effect. It’s about time the world discovered her.

A smattering of articles have noted her groundbreaking backyard experiment measuring the sun’s effect on various gases since 2011, when a retired petroleum geologist unearthed Foote’s 1856 research. But drive-by summaries paint an incomplete picture of a woman whose work and life intertwined with women’s rights activism and industrialization—the cradle of climate change.

Eunice grew up in East Bloomfield, New York. Her parents, modest farmers, scrimped together money to send her to a boarding school that offered revolutionary science classes to girls. Through her roommate, a sister to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Eunice became associated with the Cady family.

Eunice married Elisha Foote, a young patent lawyer who was also connected with Cady family. The pair began their life together in Seneca Falls, New York, where Eunice spent time inventing and experimenting in the Footes’ home lab.

As a woman, she couldn’t legally patent her first invention—a stove with a thermostat. So her husband did, in 1842. Eunice was reported as the inventor in The Lily, the women’s newspaper edited by Amelia Bloomer. Eunice was bursting with ideas she wanted to share with the world, but first, the world would have to recognize her agency as a woman. Thus began Eunice’s fight for women’s rights.

Her friend Elizabeth Cady Stanton organized the first women’s rights convention in 1848 in Seneca Falls. Eunice and Elisha both attended and signed the Declaration of Sentiments demanding the vote for women. Eunice also helped to publish the declaration in Frederick Douglass’ newspaper, The North Star.

A few years later, Eunice conducted her gases experiment. Fossil records had shown that the world had once been warm, and she wanted to know how. Eunice knew that limestone had been found to hold trapped carbon dioxide. Through her experiment, she concluded, “An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a much higher temperature.”

Eunice needed to get her discovery in front of the new American Association for the Advancement of Science. But a man would have to present her paper.

That man was Joseph Henry, the original secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Elisha Foote had known Henry since he taught Elisha as a teen in Albany. So Henry presented Eunice’s paper at the 1856 AAAS convention, and the next-day’s newspaper ran a tepid write-up admitting that Eunice “must be a charming person,” but her research “would hardly interest your readers.”

Eunice and Elisha continued to tinker in their lab, each earning patents for multiple inventions such as squeak-free rubber insoles (Eunice) and ice skates (Elisha). A few years after the Civil War, President Ulysses Grant appointed Elisha as US patent commissioner. Elisha directed which inventions would receive patents during the height of industrialization. His own brother, Henry R. Foote, earned one of the first patents for oil as a vehicle fuel—for a steamboat engine. The family of the first person to predict a warming climate contributed to its genesis.

History’s butterfly effect is wild. What if the world had listened to women of Eunice’s time? What if the world had taken her climate discovery seriously? Would people have been more cautious with their adoption of fossil fuels? Would we be struggling with human-caused climate change today?

Eunice’s story deserves space in our understanding of history. Likewise, the field of climate science demands space in public discourse. The Trump administration has taken drastic steps to erase documentation of human-caused climate change, first by scrubbing federal websites and documents of climate-change references and data, and most recently, by taking steps to shutter the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

My forthcoming novel-in-verse, Footeprint: Eunice Newton Foote at the Dawn of Climate Science and Women’s Rights, attempts to correct the record, at least for Eunice. With one notable gap.

Because history rendered Eunice invisible, we don’t know what she looked like. (Don’t Google her; many images attributed to her are actually her daughter Mary or unidentified.)

But I think I found her.

(Dudley Observatory Dedication, August 28, 1856, Tompkins Harrison Matteson, 1857. Image from Wikimedia Commons.)

A painting by Tompkins Harrison Matteson depicts an observatory dedication that coincided with the 1856 AAAS convention where Eunice’s climate paper was featured. Dozens of scientists pose stiffly in the painting, entitled “Dudley Observatory Dedication, August 28, 1856.” Many remain unidentified by scholars.

(Detail of Dudley Observatory Dedication, August 28, 1856, Tompkins Harrison Matteson, 1857. Albany Institute of History & Art. Photo by Lindsay H. Metcalf.)

One unidentified couple sits prominently onstage. The man looks like a young Elisha Foote—with the same beard, glasses, and build shown in a confirmed 1860s photograph. The woman beside him echoes Eunice’s physical description from her passport and resembles their daughter Mary.

(Photograph of Judge Elisha Foote from Wikimedia Commons.)

(Mary Foote Henderson image from Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.)

I showed the painting to historians. Leif HerrGesell, former director of the East Bloomfield Historical Society in Eunice’s hometown, called the image a “dead ringer.” Sam McKenzie, who self-published a biography of Eunice, said, “I think this is called . . . a scoop.”

Still, historians are cautious to confirm the image, and rightly so. If this is Eunice, it would be the first portrait of her ever identified. Either way, her legacy is finally visible.

It’s futile to speculate what might have happened with fossil fuels and climate change if the public had known of Eunice’s carbon dioxide discovery earlier. What is worthwhile? Making sure that climate science remains visible and accessible—while we still can.

Lindsay H. Metcalf is the author of Footeprint: Eunice Newton Foote at the Dawn of Climate Science and Women’s Rights, a young adult novel-in-verse releasing February 10 from Charlesbridge Publishing.

Footeprint

Eunice Newton Foote at the Dawn of Climate Science and Women's Rights

A fascinating novel-in-verse for young adults capturing the discoveries of Eunice Foote, a remarkable woman in science WAY ahead of her time.

Discover the extraordinary life and work of Eunice Newton Foote: The woman who identified carbon dioxide as a cause of climate change in 1856 (!) when most people preferred that women be seen rather than heard. This lightly fictionalized novel-in-verse account finally gives her the credit she deserves for her groundbreaking work.

Eunice’s most important discovery was recognizing the effect of excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere: a warming planet. But in a society driven by coal, kerosene, and crude oil, Eunice’s warnings went unheeded. After all, who would listen to a woman—especially a woman known to consort with suffragists?

From the Seneca Falls Convention to the halls of the US Patent Office in Washington, DC, Eunice Newton Foote blazed a trail for independence and inquiry. Today Eunice’s discoveries feel ever more prescient. She knew that reliance on fossil fuels would have a devastating effect. Today she is finally receiving the credit she deserves. Perfect for teenagers interested in STEM and the Age of Steam.

Be sure to check out the downloadable for a free discussion guide.

Fall 2024 Preview Recap – Enjoy Autumn With These Children’s Books 0

Charlesbridge Publishing recently held a live Fall 2024 Preview introducing all our fall titles. In case you missed the stream, here are some highlights to the preview.- Jaliza Burwell

- Tags: Charlesbridge Children's Book Publishing children's books David Biedryzcki poetry Preview reading Ruth Spiro STEM Traci Sorell

David L. Harrison wins the Society of Midland Authors Book Award 5

I just returned from Chicago and the 2017 Book Awards banquet and ceremonies, which was sponsored by The Society of Midland Authors. Wow! What a party! I was there to receive the award for the best nonfiction children’s book by a midland author published in 2016, Now You See Them, Now You Don’t. Yay, Charlesbridge!

The event was held on the penthouse floor of this building.

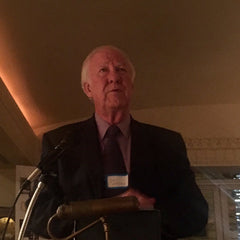

Talk about ambience! Master of Ceremonies was Keir Graff, Executive Editor for Booklist.

And here I am giving a few remarks after receiving my award.

The Society of Midland Authors was established in 1915 by a group of authors that  included Clarence Darrow, Edna Ferber, William White, and James Whitcomb Riley. Others who soon joined included Ring Lardner, Edgar A. Guest, and Carl Sandburg. Over the years the list of those who have been honored for their books is long. I noticed that among them was Kurt Vonnegut, which brought back memories of a workshop I took under him at Indiana University one year.

included Clarence Darrow, Edna Ferber, William White, and James Whitcomb Riley. Others who soon joined included Ring Lardner, Edgar A. Guest, and Carl Sandburg. Over the years the list of those who have been honored for their books is long. I noticed that among them was Kurt Vonnegut, which brought back memories of a workshop I took under him at Indiana University one year.

I had a delightful time being among the six winners honored at this year’s event (adult fiction, adult nonfiction, adult biography & memoir, adult poetry, children’s fiction, and children’s nonfiction). I posed, signed books, visited, and basically soaked it all in. The event was made even better with my wife, Sandy, daughter, Robin, son, Jeff, and family friend, Jason Gertzen there to celebrate the special occasion.

- Donna Spurlock

- Tags: animals Award winner David L. Harrison nature Now You See Them Now You Don't poetry Society of Midland Authors

A Q&A with David L. Harrison about Now You See Them, Now You Don't 0

Introduction

After Ms. Hutchens’ fourth and fifth grade students in Colorado read Now You See Them, Now You Don’t by David L. Harrison, the students brainstormed questions for the author.

Here are David’s answers! What questions would you ask him? If you’ve got questions, you can find David online at www.davidlharrison.com and you can send your questions to david@davidlharrison.com. You can also download this Q&A as a discussion guide here.

Questions from the 4th Graders

WHEN DID YOU START WRITING POETRY?

I made up my first poems when I was six years old. I decided to become a writer the same year I got married fifty-seven years ago. Well yes, I agree, fifty-seven years is a long time!

ARE YOU GOING TO WRITE ANOTHER BOOK?

Yes! I work every weekday on one book or another. I’m working on several new ones now. Six of them are already accepted to be published sometime during the next few years.

HOW DID YOU MAKE SUCH AN AMAZING TITLE?

Choosing the right title is an important job. My editor, the artist, and I all made suggestions. The final decision is the editor’s so she chose Now You See Them, Now You Don’t, but I don’t remember who thought of it. Maybe I did!

WHERE DID YOU GET YOUR ILLUSTRATIONS?

I wish I could illustrate my own books but I’m not that good an artist. I write the words and my editor finds an artist to paint the pictures. For this book the wonderful art was done by Giles Laroche who lives and works in his house in Salem, Massachusetts, and in a 230-year-old barn in southwestern New Hampshire. Wasn’t I lucky?

HOW DO YOU KNOW THIS STUFF?

I don’t! Some of it I know. When I went to college I studied science. But almost always before I start writing I must first get ready to write. Call it research. I read books and articles about my subject. I make notes to look at later. And many, many times I get fresh new ideas for my own work when I read what experts are saying. You need to do the same thing. We all do!

HOW LONG DID IT TAKE TO PUBLISH YOUR BOOK?

From the day I sent my idea to editor Karen Boss to the day I held my first copy of the new book took two years, nine months, and seven days. Does that seem like a long time to you? It was really pretty fast in the world of book publishing. Sometimes it takes twice that long!

WHAT IS IT LIKE TO BE A WRITER?

I write because it’s my favorite kind of work. I love my work! But to be a writer also means that I must have good self discipline. No one makes me get up each morning at 6:00 a.m. to get started. I’m my own boss so I alone must decide what is important to me and then see to it that I do it! Being a writer means that I get to go places in my mind that I’ll never really see. It means that I can work all day in my pajamas! It means that I am using my own imagination, my own words, my own effort to make up a poem or a new story or create a new nonfiction book. It means that I get to talk to important people, like I’m doing this morning as I read your letters!

HOW MANY BOOKS DO YOU HAVE?

I’ve had ninety-two books published and six more are on their way. Think I’ll make it to one hundred? Some of my books, or parts of them, have been included in more than 185 anthologies published by other people, here and in many other countries around the world.

WHERE DO YOU WORK?

I work in my office, which is eighteen steps from my bed, down the hall, first door on my right. Hard to beat that!

DO YOU ONLY WRITE POETRY?

I love poetry but I also write fiction, nonfiction, and books for teachers.

WHAT WAS YOUR FAVORITE SUBJECT IN SCHOOL?

I liked school, especially math and science. When I was your age, I collected all sorts of things from nature, everything from insects and bird wings to sea shells and snake skins. Today I often write about nature so you can see that writers tend to write about what they know and like.

ARE YOU COMING OUT WITH ANY NEW BOOKS SOON?

I’ve had two new books in 2016. In 2017 I don’t think anything is scheduled but there should be a cluster of them in 2018 and 2019. I don’t get to decide on when my books will come out. That’s for the publisher to choose.

HAVE YOU EVER WRITTEN A CHAPTER BOOK?

No, but I’ve thought about writing one for ages. I did recently finish a story for middle grades that isn’t published yet, and I have three more stories in mind that I hope to write over the next few years.

WHY DOES THE FLOUNDER HAVE TWO EYES ON ONE SIDE?

So it can see its food swimming nearby. Nature has given the flounder this advantage. It’s hatched with two eyes where they should be but as it matures one of the eyes slowly moves to the other side. That way the fish can lie hidden on the sea floor and keep an eye out (well, keep two eyes out) for something yummy to swim by.

HOW MANY TIMES HAVE YOU BEEN REJECTED?

Hundreds! I was turned down 67 times in a row before I sold my first story in 1962. I still get rejected all the time but not as much as I once did when I was learning how to write. A writer never knows what an editor might need so sometimes I get lucky and sometimes I don’t. You just have to know that being rejected is part of the business of being a writer. No use crying about it or having a pity party. You try again with a different editor. This week I sold a book to an editor who turned down the idea a year ago because her situation has changed and now she can use it.

DID YOU TRAVEL TO AFRICA?

No, sadly. I always wanted to go there but so far it hasn’t happened. But I’m young. There’s still plenty of time!

HOW LONG HAVE YOU BEEN WRITING?

I started writing stories for adults in 1959. I was twenty-two years old then. Ten years later, when I was thirty-two, I wrote my first book for kids. It’s called The Boy With a Drum. You can still find used ones on Amazon.com. It sold more than two million copies. Because of it I decided that I should try more books for boys and girls. Other than marrying my wife, it was the smartest thing I ever did.

HOW MANY BOOKS CAN YOU WRITE IN A YEAR?

I try to work twelve hours each day five days a week, so I write a lot! A new book takes me anywhere from a month to two years, depending on what it is, how long it is, and how much research I need to do before I begin to write.

HOW DID YOU COME TO LIKE POETRY SO MUCH?

Poetry is fun to write. It’s a game you play with words, trying to find just the word you need and putting into the line where it belongs. I like to write all kinds of poems from silly to serious and from short to long. It’s fun to read poems aloud too.

WHEN DO YOU THINK YOU’RE GOING TO STOP?

You sound just like my wife! My standard answer is that I’ll write as long as I can lift a pencil and remember what it’s for.

WHAT IS YOUR FAVORITE BOOK YOU’VE WRITTEN SO FAR?

That’s a tough one. It’s usually the most recent book so I’ll pick Now You See Them, Now You Don’t.

HOW OLD ARE YOU NOW?

I’m seventy-nine. Oh my gosh! Did I say that? Please don’t tell my wife. She thinks I’m twenty-six!

HOW DOES IT FEEL TO BE FAMOUS?

It feels wonderful to be famous! At least that’s what I hear. I wouldn’t know. Some of my books are fairly famous though, and that’s close enough for me.

WHERE HAVE YOU BEEN IN THE WORLD?

Most of the states, Canada, Mexico, Virgin Islands, Europe, Malaysia, South America . . . . One time I went to talk to kids in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. I got there by flying east across the Atlantic Ocean and returned home later by coming across the Pacific Ocean and back across America. I went all the way around the world to visit with kids in school. So now you can see who is important. You are!

Questions from the 5th Graders

WERE YOU ALIVE IN 1963?

Yes, I was alive in 1963. That year I blew out twenty-six candles on my cake. My daughter Robin would have been a messy three-year-old helping me, and her bratty brother Jeff hadn’t been thought of yet. My first job was in a biology lab in Evansville, Indiana where I spent days working with mice, rats, and such. Yes, I got bitten a few times. Yes, it hurt. No, I didn’t care for that.

WHY DID YOU SWITCH CAREERS?

The reason I left science was to find a job that would give me more opportunities to work on my writing. I wasn’t a very good writer yet but I wanted to be. I guess it worked out. Now You See Them, Now You Don’t is my ninety-second published book and I have six more that I’m working on.

HOW DO YOU WRITE YOUR BOOKS?

I’ve talked to a lot of grownups in my life who didn’t ask questions as thoughtful as yours. The secret to my writing? Here it comes. I get ready to write before I write my first word.

I’ll use the book you read as an example.

One day in April, 2013, I sent a note to an editor at Charlesbridge Publishing that said, “I want to write a collection of poems about animals that use natural camouflage and have written the first three to show what I mean. I’ve listed a couple of dozen animals representing eight classes. I’ve attached the poems.” The three poems I sent were octopus, polar bear, and walking stick. And notice that I also included a list of other possible animals to include and they came from different groups: mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and so on.

The editor liked the idea and about three years later it became a book. But long before I mailed that letter, I had been reading about animals that use camouflage. I read a lot of books, looked at pictures, made lists, and thought about how I wanted to do the writing. I decided that these poems would have a lot of science in them and that I would also add a short note about each one in the back of the book. I began making lists of what I wanted to know and keeping folders of notes about each animal that I added.

HOW DO YOU KNOW WHAT TO WRITE ABOUT?

One thing I love about the time before writing begins is that I always discover such fascinating information. I’ll be looking for one thing and find something else entirely that I never dreamed existed. That really gets me excited! And it helps me make my writing more interesting for you. I also learn the right words to describe my subjects. What sounds they make. What their babies are called. The better you prepare, the more you learn. The more you learn, the better you write. It just makes sense, doesn’t it? Not only that, I get to learn about animals I’ve never seen, places I’ve never been, and thoughts I’ve never thought before.

HOW DO YOU KNOW WHEN TO WRITE A STORY (OR A POEM)?

That usually isn’t a problem because I start out to do one or the other. But there have been times when I thought I wanted to write one and changed my mind about it after I did my homework. Another time I set out to write a nonfiction book about mountains. While getting ready for it I kept reading about the important role that glaciers play in shaping and tearing down mountains. When I finished the first book, I decided to write one about glaciers. While getting ready for that one, I kept reading about how some of those big glaciers had been a problem when the first people to arrive here 15,000 years ago couldn’t get around them to move farther south where it was warmer. So when I finished the glacier book I wrote one about the first people.

HAVE YOU EVER STRUGGLED WITH WRITING A BOOK?

Sure. Writing rarely goes as smoothly, quickly, or easily as you might expect. It’s hard work getting writing right. Now You See Them, Now You Don’t took three years. Mammoth Bones and Broken Stones took five years. The Mouse Was Out at Recess took nine years. But this is an important part of the reason why I love writing. If it were too easy, there would be less pride in getting it to work! I get up every morning at 6:00 a.m. and try to write for twelve hours that day. No one makes me do this. I do it because I love it that much.

- Alaina Leary

- Tags: animals camouflage David L. Harrison life science nature Now You See Them Now You Don't poem poetry